Why investing in the "next big thing" is so hard

An excerpt from Low Risk Rules: A Wealth Preservation Manifesto

There is an ever-present temptation to buy shares in the most exciting, fastest-growing companies. Many novice investors assume that the only way to grow your portfolio is to buy shares in companies that are growing at high rates. The evidence, surprisingly, shows the opposite.

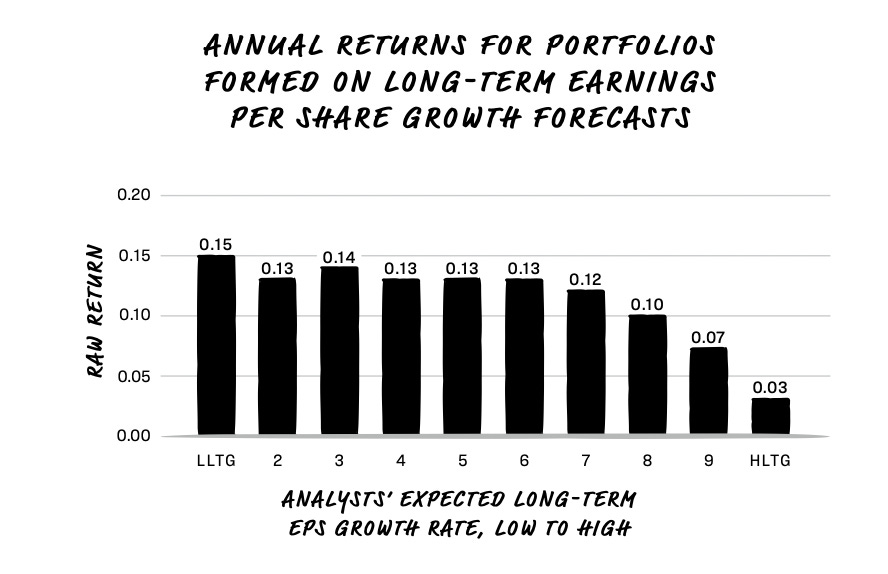

In the December 2019 Journal of Finance paper “Diagnostic Expectations and Stock Returns,” researchers confirmed a 1996 analysis showing that “returns on portfolios of stocks with the most optimistic analyst long term earnings growth forecasts are substantially lower than those for stocks with the most pessimistic forecasts.”

Huh?

You’re telling me that the companies expected to grow earnings the most performed worse than companies with the most pessimistic earnings forecasts?

That’s exactly what I’m telling you.

The paper is a dense one, with over fifty pages full of formulas and charts, but it is summarized neatly in the following chart, which is based on analyst estimates and market data collected by the researchers between 1981 and 2015. The universe of stocks is segregated into deciles, with the lowest projected earnings growth rates on the left, and the highest on the right. The subsequent return is reflected in the bar length. Reliably, over time, the stocks that analysts believe will exhibit the strongest growth actually perform far worse than the stocks that have the lowest growth projections.

To the non-professional investor, this makes no sense. You might be asking: “Isn’t the whole idea of investing to grow your capital by identifying the fastest-growing companies?” You might think that searching for the next Google is the ideal way to build your portfolio, but as the researchers demonstrated, it’s not.

Why is this? Well, a big reason is that higher-growth companies are more expensive than lower-growth companies. This is because investors are anticipating this growth, and therefore bidding up the prices of these companies. And so for an investor to earn a premium return on their money, the company needs to not only grow fast, but to grow at a faster rate than the market expects.

And here’s where things get difficult. The vast majority of high-growth companies do not maintain their growth rates. Portfolio manager Steven Romick highlights this by analyzing data between 1979 and 2020. He takes the top 1,000 uS companies with over 10 percent earnings growth, and looks at how many of them were able to maintain this growth over subsequent years. Only 353 of those companies maintained a 10 percent growth rate in the subsequent year. After three years, only seventy-four of the original 1,000 were left. And after five years, only twenty-one remained. And because most basic stock analysis seems to be nothing more than extrapolating recent growth into the future, most growth companies will disappoint.

Chasing individual growth names is hard, but just as difficult is the temptation to chase fads. The idea is the same—identify an area of promising growth, and make some big bets on it.

The thing is, investors don’t call them fads. They are “theme investing strategies,” “new paradigm” companies, or “new economy” stocks. They are the companies of the future operating in the industries of the future, and anyone casting a skeptical eye on them is behind the times.

And unfortunately, as the exchange-traded fund (ETF) and indexing industry has thrived, more and more products are created that are intended to capitalize on these fads. Just because a fund company creates an ETF for a new hot investment area, it doesn’t serve as validation of that idea. It’s just a symptom of a business that will package and sell anything that people will buy.

In a 2021 research paper, Ben-David, Franzoni, Kim, and Moussawi track the performance of “specialized ETFs that track niche portfolios and charge high fees,” concluding that “these products perform poorly as the hype around them vanishes, delivering negative risk-adjusted returns.” Quantifying their analysis, they show that “specialized ETFs persistently generate negative alphas of about minus 3.1 percent per year.”

Recall that “alpha” means investment outperformance versus your benchmark. So, yup, that means that these strategies, on average, underperform the broader market by over 3 percent per year. That’s huge.

Before leaving this topic, I thought it would be fun to revisit some of the larger investor manias in recent history. You may have read about the tulip bubble of 1637, the South Sea bubble of 1720, and the 1840 frenzy around investing in railway stocks, but recent history suggests that a knowledge of history and a supercomputer in your pocket may not help you avoid the follies of the past—in fact, there’s an argument that social media has thrown accelerant on the fire of bubble creation.

Here is a partial list of some recent speculative frenzies and the approximate years of each. Be honest. How many of these did you take part in?

Nifty Fifty stocks (1967–1972)

Japanese real estate (1980s)

Tech/telecom (1996–2000)

Oil (2008)

Housing (2008)

Rare earth metals (2010)

Fracking (2011)

Biotech (2012–2015)

3D printing (2014)

Marijuana (2018–2019)

Crypto/NFTs (2021)

There will always be a hot new investment fad. A new paradigm. And those of us who cast a skeptical eye will be seen as hopelessly behind the times. But even when the predictions are correct, there’s no guarantee that investors will make money.

Chasing growth is hard, and you should try to resist the urge to do so.

Because there is a much better way.

Want to know more?