The Allocator Problem Part 1: Layers upon layers

The allocator model is great for the investment industry, and less so for investors

Simplicity has been difficult to implement in modern life because it is against the spirit of a certain brand of people who seek sophistication so they can justify their profession.

NASSIM NICHOLAS TALEB

There are several basic ways you can go about building a portfolio.

1. You can buy stocks directly.

2. Or, if you decide you don’t have the skill, time, or temperament to do it yourself, you can hire a portfolio manager to do it for you.

3. Or, if you decide that you’d prefer to spread your money around to different managers, you might end up with something that looks bit like this:

Now things are starting to get a bit unwieldy. Depending on how many managers you’ve got, and what kinds of different strategies they are employing, you may or may not actually be well diversified. If they’re all doing the same basic thing, and owning the same basic stocks, you might be better off with a single manager.

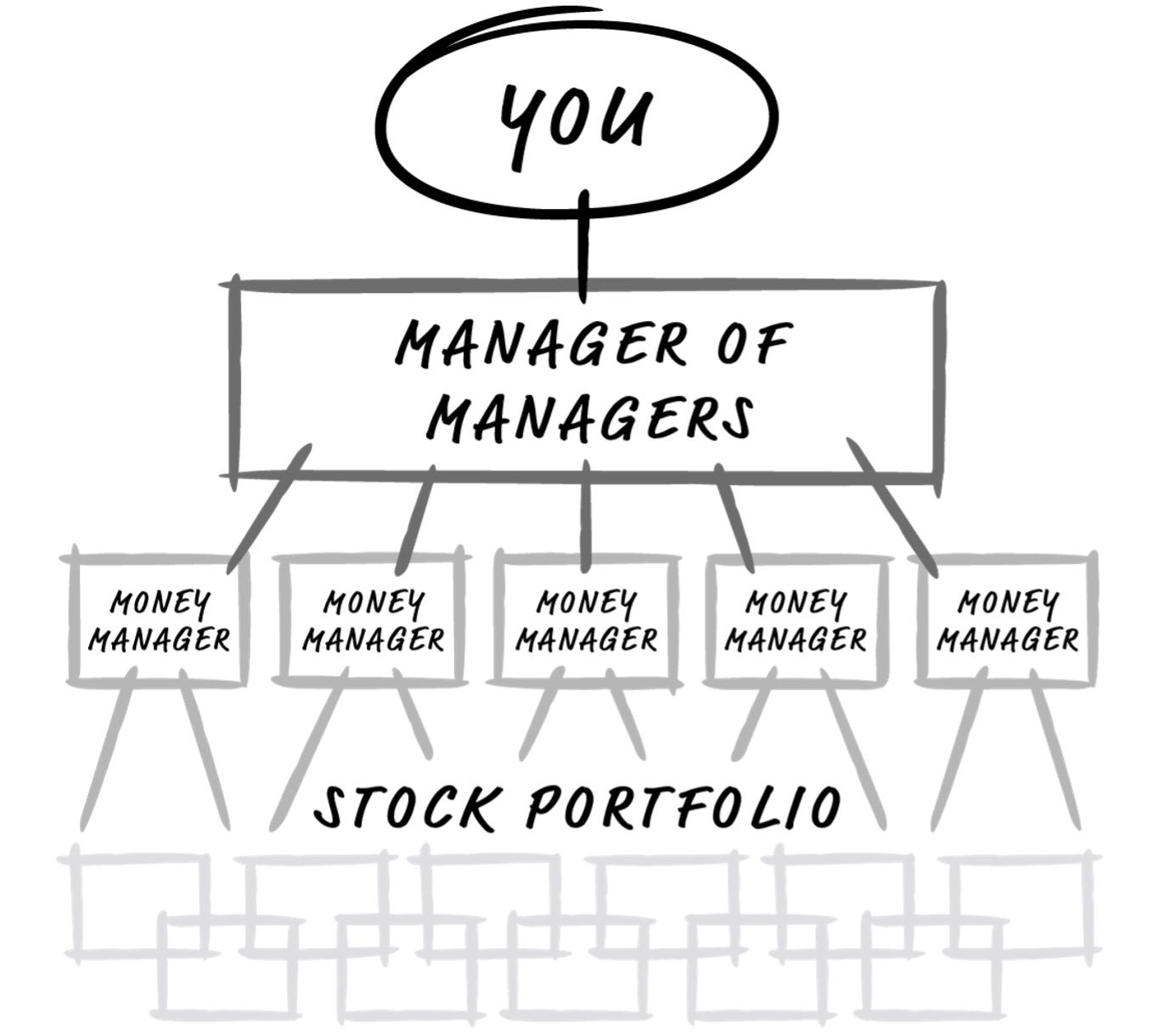

4. And so now there’s some coordination required. You might find that you need someone on top to oversee the managers. And now the portfolio looks like this:

They go by many names—“managers of managers,” “virtual chief investment officers,” and too many more to name. But they all share one thing in common: none directly manage client assets. They all farm the job out to external managers.

For the sake of simplicity, let’s call them “allocators.” This is because they don’t actually invest your money, but rather “allocate” it out to specialist managers who they hire to manage your funds on their behalf.

The model comes from the institutional investment world, where boards and investment committees are filled with professionals who volunteer to help an institution oversee money invested on behalf of its ultimate beneficiaries—a pension or endowment fund, for example.

These board members, while concerned with investment performance, are really more worried about getting sued by donors and/or beneficiaries.

And so they hire a professional consultant to guide their decisions. It’s mostly a “Cover Your Ass” exercise. There is a theatrical element to these quarterly meetings. The consultant will explain the minutia of a particular manager’s performance over the prior three-month period, and a boardroom full of executives will nod along. The consultant looks for reasons to replace a manager or put them “on watch,” so as to give board members assurance that someone is closely monitoring the underperforming segments of the portfolio. The exercise repeats for each portfolio manager, and then repeats again each quarter.

Does the exercise actually contribute to investment returns? In a 2014 paper titled “Picking Winners? Investment Consultants’ Recommendations of Fund Managers,” Jenkinson, Jones, and Martinez conclude that they “find no evidence that these recommendations add value, suggesting that the search for winners, encouraged and guided by investment consultants, is fruitless.”

So… there’s that.

These boards tend to be full of successful individuals who also often happen to be wealthy, and so the industry began to offer the same model to wealthy families. The basic pitch is that they will help you hire the “best” managers in each asset class. And while it’s dressed up in a veil of exclusivity, it’s simply a close sibling to the stockbroker who builds you a portfolio of mutual funds.

They will recommend a bunch of different managers, diversifying among different styles. Let’s have a growth manager, a value manager, a large-cap, a small-cap. Oh, and add a mid-cap, maybe an emerging markets specialist…

And on it goes. At the end of the day your portfolio has become so diversified that it becomes just another index fund—but with much higher fees.

Experience tells us that portfolios built by allocators perform no better than lower cost portfolios. In some cases, they can do far worse. Why, then, are they so popular in the “high net worth” segment of the wealth management industry? I’ll expand on that next week.